Part One: Mental Struggles on the Wall

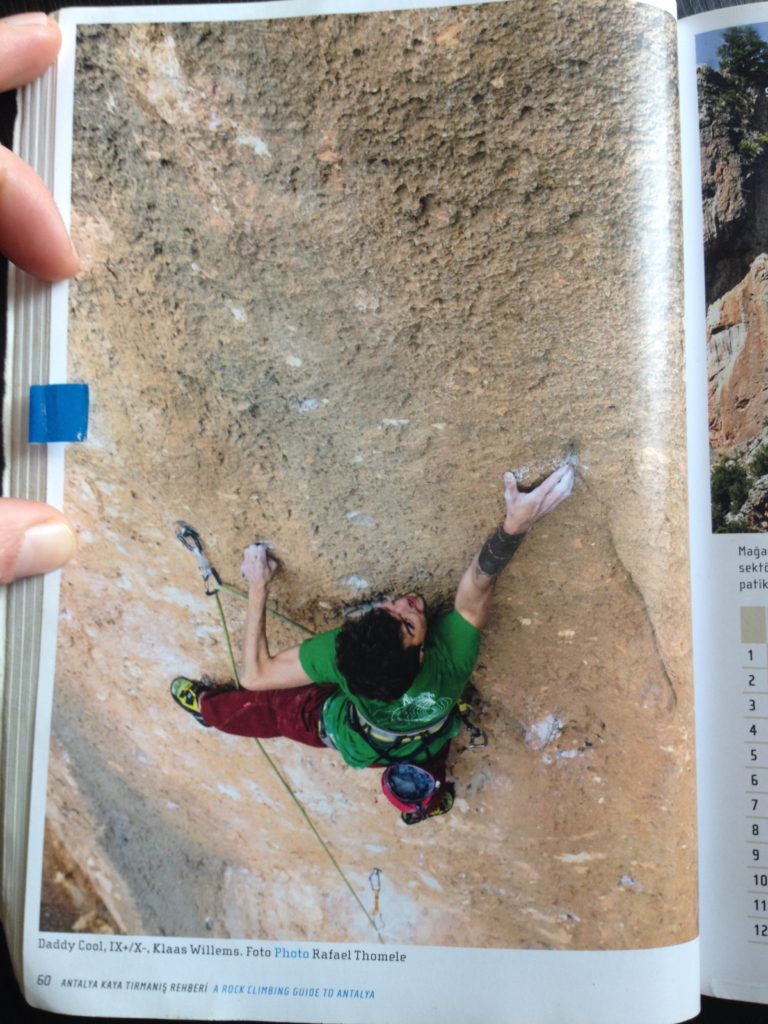

Two weeks before my flight back to the US in April 2017, a small crew of awesome women and I walked up to one of the walls above our camp to get on a route called Daddy Cool. For all of us, the first goes went superbly well. Later in the week, I received two mediocre catches from two different belayers when falling from the middle of the crux, landing hard on the slab. Around the same time, my relationship with my Turkish climbing partner slash Significant Other took a nasty turn, leaving me distraught. On moves where I had once felt so powerful, in situations where I used to feel so confident, I felt utterly timid and tiny. Logically, I knew the route was within my abilities, having one-hung it several times. Yet, I couldn’t pull myself together and make it happen. What’s worse, I stopped believing I could do it. In the evening on my last day, I tried again. It was drizzling, but I still managed to highpoint. For the first time in my life, I shed tears while cleaning my draws off the wall.

Returning to the US in late April 2017 gave me a wonderful opportunity to reflect on my climbing. My anecdotal self-assessment seems to show that in a year of climbing, my physical strength grew more quickly than my mental strength. One of my biggest weaknesses in climbing is my inability to remember beta, describe it to others, and understand other people’s beta. There were hints, in fact, there was a lot of evidence that I’m lacking in this respect. Other people’s descriptions of moves and instructions for cruxes baffle me and usually go in one ear and right out the other. Good for keeping a calm and empty mind, right? I have onsighted higher grades than I’ve flashed. I’ve learned to defer to someone else if a friend or partner asks about beta for a route; in the past, my information has been totally useless – and even detrimental – to others. I tend to climb intuitively and can usually see holds and create movement without labelling them or planning in advance. This serves me well in onsighting, in setting, and improvising on-route when climbing below my physical limits. I always try to climb the most efficient way possible and climbing at my physical and mental limits makes me feel ecstatic. So, the more skills I learn, such as remembering, describing, and understanding beta, the more I can climb.

In May 2017, I climbed at Smith Rocks State Park for the first time in five years and really struggled with the long, technical routes. Not only because my technique was lacking (though this too), but also because I strained to remember sequences. The communal cloud of knowledge from climbers could be at my fingertips, slicing the time it takes to send projects into pieces and saving precious skin. Instead, I found myself laboring to remember full sequences, relying on pure repetition to hammer the beta into my thick skull. In the spring, I decided I wanted to actively improve my proficiency and ability to rehearse beta in my mind. But, I didn’t really have any concept of how to move forward with this.

At the Fins, the white sheer limestone made it tough to read routes from the ground and beta was unique and crucial.

Photo: Dylan Connole

After some time on the lovely limestone in the American West, I spent the fall climbing in the Red River Gorge. In the Red, I usually made an equal number of hand and foot movements. Beta there was not overly important because the routes weren’t particularly complex. As always, I did my best to find the most efficient way through my projects, selecting better feet options for my size, using a half dozen unchalked holds in the redpoint crux of Cat’s Demise. Crowd-sourced knowledge served me well (thanks ya’ll for the local old man beta!) too. In the evenings and mornings, my partner quizzed me on my projects, encouraging me to talk through each of moves aloud. In my 10 months state-side, I made baby steps, a bit of micro-progress, towards becoming a better climber in this respect. When I arrived in Turkey this March 2018, one of my goals was to send a route that shut me down before I left for the US, Daddy Cool (8a/13b). It has a long crux up high, full of interesting moves I could still describe in detail…or so I thought.

Part Two: Dancing up Daddy Cool

This year, getting back on this route was my only real climbing goal for this season. I felt prepared to put up Daddy Cool. One of my biggest improvements in my climbing in the last year has been my head game. I can tell that I’ve gotten stronger, but most importantly, I’ve feel like I’ve gotten better. On the wall, I feel more confident, more competent, and have a better understanding of my body and its abilities. I didn’t climb much in December, January, or even in February, so the plan went something like this: a few days of longer pitches to adapt to this style of limestone and sport climbing again followed by a focused attempt to get my revenge.

So much for easing in and adapting to the climate – two days after landing Antalya, Turkey, I went straight to the project:

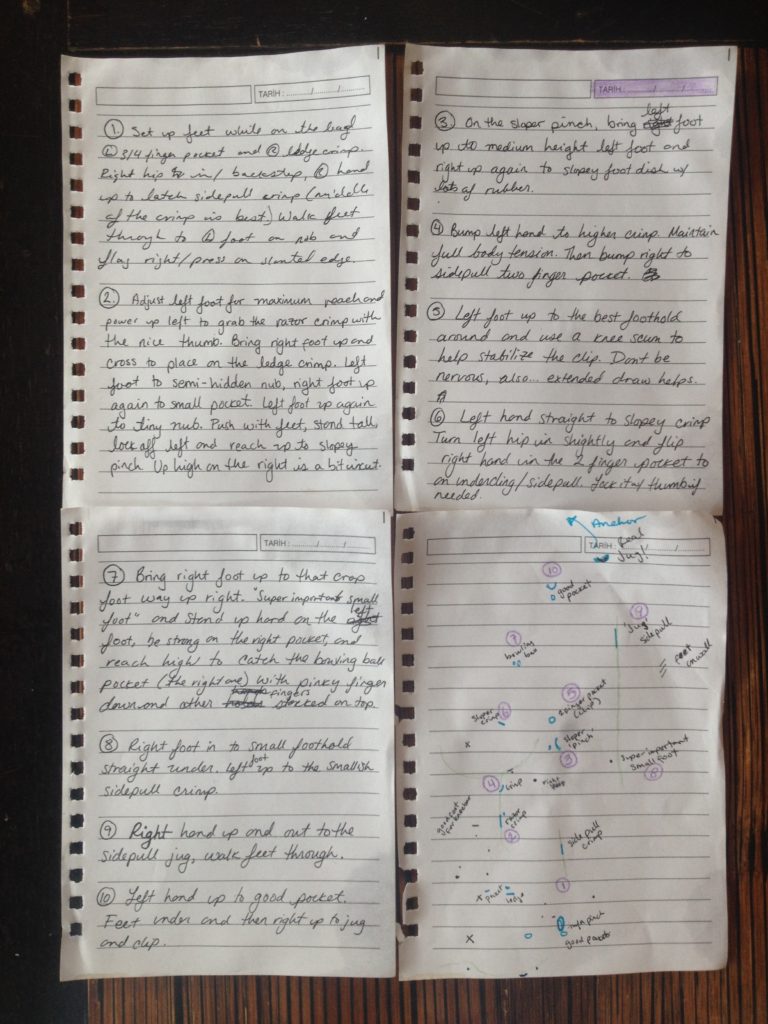

Daddy Cool 8a(5.13b) is a 30m long route in Anatolia, an east facing wall with shade until mid-day. The first half of the route feels like a techy 7a/11d. The moves require accurate foot placement and good balance. In the middle, there’s a no-hands rest and jugs followed by two more bolt lengths of moderate climbing. The crux begins with longer, more powerful moves between small but incut crimps and delicate footwork, leading to a tough and frustrating clip at a fixed draw. The beta splits, with equally difficult options left and right on small holds with bad feet. The crux ends on a good three finger pocket and a right-hand jug one bolt before the anchor.

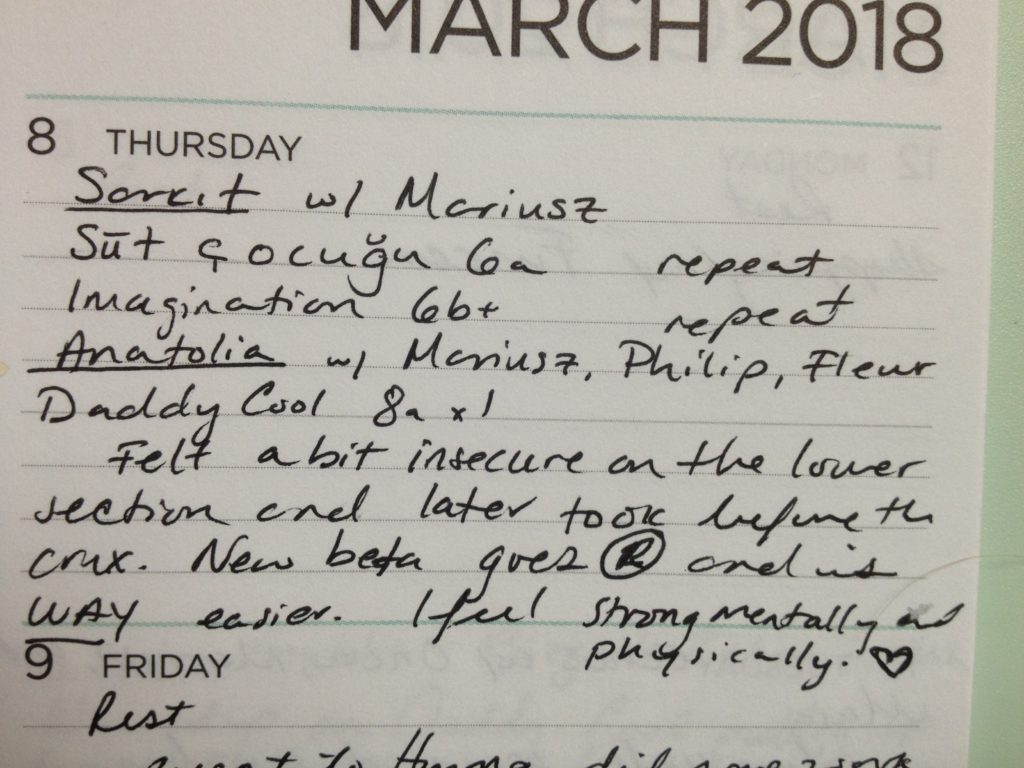

March 8th, 2018: As we walked up to the crag, two acquaintances had just put up most of the draws on Daddy Cool. My burn went well. I found new beta for the crux, choosing to go up to the right instead of left. And my suspicions about being mentally and physically stronger were confirmed!

March 10th, 2018: I tried Daddy Cool again in the morning, as my first route of the day. I felt rushed and unsure about the new beta. I forgot to move my feet up before the long reach up to the sloper pinch, and just barely stuck the move. Scrapped the next few moves together, including the tough clip, but fell from the reach to the bowling ball pocket. Solution: four individual foot movements for every one hand move.

March 11th, 2018: Because the route is in the full sun from 1pm onwards and spring is in full swing here, it’s best to climb it in the morning. Turkish style climbing doesn’t usually involve getting up early. Nevertheless, I was able to convince a friend to come with me in the morning for one burn. As I entered the crux, I felt strong and solid. Three moves in, I forgot to move my feet up and fell going to the two-finger pocket. It’s a small move that requires precision. I wrote in my climbing journal: Beta memorization is a big problem.

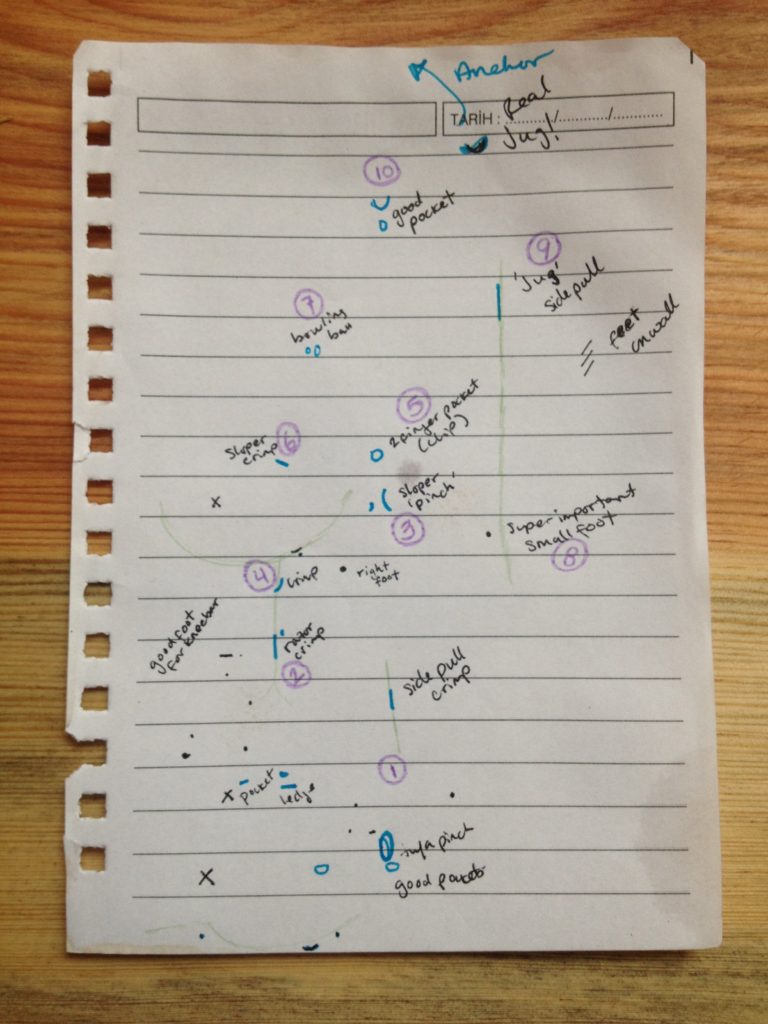

My next two climbing days were spent elsewhere, but I couldn’t get the route out of my mind. One of the wonderful things about this climbing area is the community. Seven camps for climbers are spread over a 20-minute walking distance. Many people come here alone and find partners in the camps. My personal favorite is Climber’s Garden, which has a wonderful communal kitchen and living room. Discussing my dilemma with a slew of climbers from all over (Israel, Germany, Canada, Turkey), I decided to try to draw the crux and write out the moves. The top suggestions from others were to draw a map of the crux, using different colors for hand and foot holds. Then, to label the holds and describe the moves in words.

Drawing the map did not come naturally to me. Even though I had been on the route a dozen times, it was tough to remember all the feet and to place them in a more or less accurate location relative to the other holds. I’m a sociolinguist and I think in words, not pictures. Writing out the moves was a bit tedious. But, the words describing the moves flowed out of me in a way that the map did not.

Armed with cheerful motivation from good days climbing elsewhere, a better understanding of the beta, and a partner willing to head out in the morning, I went to give Daddy Cool another shot. The draws were gone, so I hung mine on the route as my warm up. Somehow, I high pointed. The first section of the route felt like a smooth dance. On my second go, I climbed in that famed ‘flow state’, relaxed and secure. At the point where I fell before, I forgot to bring my right foot in. The left foothold broke. I hung from two small pockets for a moment, trying to bring my feet up to thigh height. I let go.

The sun was already hitting the wall. Sweaty fingers on sharp crimps do not a fun time make. Roasting feet in tiny black rubber shoes also make it hard to relax while climbing. Even though I’d already climbed the full length of the route twice, I was ready to go again. After just ten minutes on the ground and two trips to pee (nervous!), I tied back in to the rope and started dancing up the delicate face.

At the move where my foothold had broken, I remembered to bring my right foot in and under me. I pushed hard on the smeary foothold to drive my body up and to the right. Both my legs were shaking. I stuck the move on point for the first time, finally making it through the crux. At the ‘real jug’, it took a minute slow and steady breathing for my legs to stop shaking. Though I wasn’t terribly pumped, I rested and shook my arms, wanting to climb the last bolt length to the anchor solidly and truly enjoy the last few moves of climbing. More than any other emotion, I felt relief. And joy.

Part Three: Becoming Better, not just Stronger

One of the most wonderful moments of projecting a route is the realization that it is in fact possible; the transformation of an impossible objective into a true potential. I never had this feeling on Daddy Cool. From the first go, I felt that it was within my ability. There was beta to be sussed and it took me a few goes to find a way to clip the draw in the crux, but I always felt that I could climb it. I always felt that I could climb it well. Perhaps it was this expectation that brought me down.

In projecting, there are many barriers to overcome before success. Finding the most efficient movement is a logical process. You can ask friends and mentors for their beta and advice as they watch you. Physical capacity is the most obvious limitation to climbing a route gracefully and cleanly. Yet mental strength and stamina are equally important. I grossly underestimated the amount of mental strength I needed for this route. As I climbed, my emotional stress clouded my mind and made it really difficult to remember the finnicky beta for the four-meter-long upper crux (so many foot movements!). I’d climbed it so many times (upwards of 14 tries in total), the sequences slowly became wired in my brain. Falling after the clip slipped into my sequence too.

Even the tiniest glimmer of hope can be enough to incite dreams of smooth climbing on moves that had before felt so tough or were simply undoable. These whiffs of success are usually enough to sustain my motivation to try a route for a few days (six times or so), even if I haven’t done all of the moves or made significant links. Logically, hope for Daddy Cool was always there. Yet, an overwhelming feeling of resignation confused my confidence; I slipped into the bad habit of thinking that actually clipping the anchor would never happen.

Besides deep breathing and attempts to quiet my mind, I don’t have many tricks in my bag to help with these types of mental challenges. Building a beta map turned out to be supremely useful. The process of drawing the map hardwired the moves in my mind, even when I made micro-changes, and helped me erase the fall from the beta. Once the moves were deep in my mind, it removed one layer of stress as I climbed.

A few days later, I belayed a friend as he worked his way up the same tiny crimps and weird footholds. I’m not sure I’ve ever grinned so much while belaying and more than anything else, I wanted to climb it again. When he came down, I was able to explain my beta to him in a way he both understood and found helpful. I came to Turkey this year wanting revenge on this route, but I came away with something much sweeter.

Great article! When will you have a climbing workshop?

Thank you Warrior Princess! I’m hoping to schedule a women’s workshop for the 19th of May. Keep an eye out online and in the gym for when we announce the final date!

Thanks for sharing my experience! I look forward to coming back to Cleveland this May and hearing all about the trip out west.

This was a great read! Thanks for sharing Tanager! I really admire your climbing and thanks for sharing insight into this process and journey for you.

The mental component of climbing can’t be overstated. Thanks for bringing it to the forefront and maybe someone will find it helpful.